Click on these links for: Part 1 Part 2 Part 3

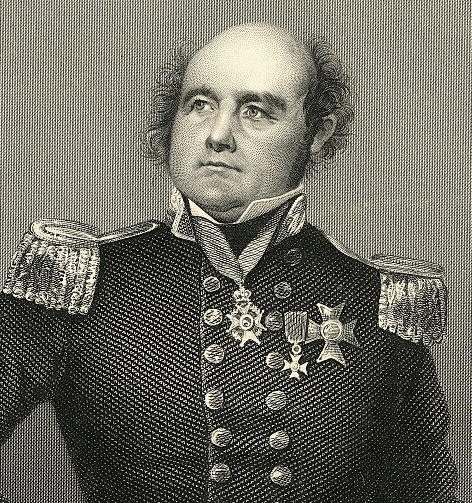

In January 1837, Sir John Franklin (1786 – 1847), arctic hero and explorer, succeeded George Arthur (1784 – 1854, Australia’s longest serving colonial governor) as governor of Van Diemen’s Land.

Many of the free settlers hoped that the autocratic regime they had tolerated under Arthur would become more liberal under Franklin. The island was still a vast penal colony with a population of nearly 43,000, of whom 17,500 were convicts under sentence. Most of the convicts were privately assigned for work in construction, farming, fencing or domestic service. Those under hard labour were sent to public service on road gangs or logging.

Not every free settler was granted the assignment of convict labour, but those who were acknowledged that the forced labour of the convicts made a significant contribution to their personal wealth and the increasing prosperity of the colony. For those colonists, the convict system under Governor Arthur was largely considered a success, and they felt his autocratic, invasive method of governing maintained the safety of all free people on the island.

Many other settlers, however, resented Arthur’s interfering in the developments of the colony’s pastoral, agricultural and industrial enterprises, and so were not as readily granted convict labour, reducing their capacity to share equally in the prosperity of the colony. This body called for the power to elect members of the Legislative Council, to create a representative government.

They also called for the end of transportation.

Arriving in 1836, John Franklin, unlike Arthur, was not accustomed to administration of a penal settlement, nor any civil office and so was heavily controlled and guided by the Arthur faction that remained. These were Arthur’s appointed public servants who continued to run the colony – the key figure was John Montagu. He arrived in Hobart on the same ship as Arthur in 1824 with his wife – who was Arthur’s niece. Montagu wielded power early on, being appointed private secretary to Arthur (1824), Colonial Secretary (1825, 1834 – 1841), Clerk of the Executive & Legislative Councils (1826) , and Treasurer (1832).

Franklin’s troubles really came to a head with the introduction of the convict probation system in 1839 for male convicts and 1843 for female convicts. The plan was that instead of being assigned to private settler or public service work on arrival in VDL, the convict would serve a term of probation in a government institution. The duration of the probation depended on the length of the original sentence. During this incarceration period the convict would receive compulsory moral and religious instruction, as well as being taught to read and write.

The women would be taught domestic skills, the men farming and labouring skills. There were more than 80 probation stations around VDL, including on Maria Island. In Hobart the women were kept in the Female Factory at South Hobart. The Campbell St barracks just at the edge of the CBD was for male convicts and intended only as a staging point before they were sent out of the city to remote probation stations, farms or road gangs.

At the end of the probation period, the theory was that the convict was now reformed and would be suitable to work for wages as a pass holder in a settler’s farm, home or business. After a period of good behaviour, then a ticket of leave could be granted, then a conditional pardon.

It was experimental and was modified many times until it was abandoned with the eventual abolition of transportation in 1853.

The probation system was perceived as better than assignment, as it had a focus on moral reform – because it was assumed that all convicts were of low moral character and just needed a good example to set them straight. The assignment system had been a punitive system that the administration relied on for economic productivity. This sounded too much like slavery, which was a hotly debated topic in England at the time.

The probation system was seen to be taking the moral high ground, as a more civilised way to treat criminals.

What it did was to cause the political and economic climate in VDL to take a distinctly different turn.

The probation system deprived the colonists of cheap labour and delivered large groups of idle, unemployable convicts to undeveloped regions of the island. Plus there was the public agitation of the Anti-Transportation League, formed in VDL in 1844.

The probation system turned out to be a disastrous failure – poor administration and planning, underfunded, overwhelming numbers of new arrivals topped off with an economic depression. No one wanted to employ the passholder convicts so the state was still responsible for their food, clothing and accommodation.

Added to this was the pressure from London for the colony to bear an increasing amount of the cost of the probation system, including the costs of transportation.

John Franklin’s successor, John Eardley-Wilmot (1783 – 1847) oversaw the end of the probation system which was also the end of his political career .

The majority of colonists had turned into vocal and active opponents of transportation and felt they didn’t have enough say in the way the colony was being managed.

The final straw was the mass walk-out of half of Wilmot’s Legislative Council, those who became known as the Patriotic Six. They were six of the eight civilian, appointed members of the Legislative Council. The names of the rebels are Richard Dry, Michael Fenton, Thomas Gregson, William Kermode, John Kerr and Charles Swanston.

When they resigned their positions on the Legislative Council it left Eardley-Wilmot unable to pass any new laws or approve a new budget.

Read on – in Part 5 you will find all the details about how their walkout lead to the first elections in VDL.